“To Measure is to Know” – Lord Kelvin

Social capital is a slippery term whose conceptualization generates a lot of controversy and debate. The proliferation of scholarly articles on this topic has grown in the last decades, including a Methodological Note in Gaceta Sanitaria by Villalonga-Olives and Kawachi (Villalonga-Olives and Kawachi, 2015), where they discuss the different definitions of social capital. A new article in Gaceta Sanitaria by Carrillo Alvarez and Riera Romani (2016) has shed more light on the topic of social capital by highlighting the different ways to measure social capital on three levels: macro (countries or regions), meso (local areas, such as neighborhoods or organizations) and micro (individuals).

Carrillo and Riera begin their paper by summarizing the origins of the concept and the two main sociological schools of thought that have worked on this topic (Bourdieu and Coleman/Putnam) and how these schools have been materialized into two different conceptualizations of the term: a social cohesion and a network-based approach. Following the latter, the authors further delineate the different subconstructs, components, and scales of social capital. The authors cogently argue that with such a complex network of concepts, “using systematized social capital measures will allow to gain a stronger foundation on how the associations between the different aspects [of] social capital and each specific health outcome occur […]”. The rest of the paper is a concise but thorough guideline to the measurement of social capital at the macro, meso and micro levels, further distilled in Table 1.

This paper offers useful guidelines for scholars interested in the measurement of social capital, with particular emphasis on its use in health studies. Measurement error is a pervasive form of bias in epidemiology that has gotten less attention than others such as selection bias or confounding. Only recently has literature emerged on how to incorporate this type of error in the hegemonic framework for causal inference, the potential outcomes framework(Edwards et al., 2015). Therefore, any improvement in the measurement of social capital and all efforts in systematizing such measurement are welcome and will improve the quality of future studies.

One specific insight I would like to add to this paper is to re-emphasize the importance of theory, in particular stressing the importance of taking into consideration the differentiation that Carrillo and Riera make in the first few paragraphs of their paper: social capital as a part of a dynamic conceptualization of society, one that changes through struggles and conflict (Bourdieu) versus social capital as a part of a static conceptualization of society (Putnam, Coleman), where capital encompasses social cohesion that includes the absence of conflict (as defined by Kawachi and Berkman). While this may seem as exclusively an academic discussion on theoretical concepts (and we have had a few of these discussions (Carrasco and Bilal, 2016a, b; Lindström, 2016), I would argue this has profound implications on the ways to measure social capital. If we assume Bourdieu’s definition of social capital, the measurement process needs to incorporate the dynamic nature of the concept. For example: adopting a dynamic view of society explicitly requires the researcher to consider that each individual is part of a bigger entity (the society) where a relational approach is fundamental(Cummins et al., 2007). That is, social capital does not “exist in itself”, and only exists because it can be spent on “something”. Much like economic capital, social capital only acquires meaning within a certain societal arrangement (Bourdieu, 1986). Therefore, while this form of capital is accrued by individuals, it only makes sense when it is related to groups (see the examples in heading 6 of this paper(Carrasco and Bilal, 2016b)). On the other hand, a static view of social capital can exist in itself, and leads to measurements that do not require of the collective for the inferences to be interpretable.

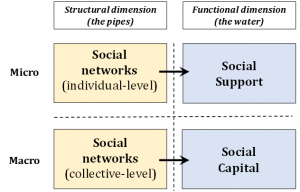

To exemplify how important these differences are, take a look at the figure below, redrawn from Thomas A. Glass, PhD.

It shows a conceptualization of social capital as the “water that flows through the pipes laid out by the social network of society”. Importantly, in this conceptualization, social capital in itself does not require of individuals for its measurement (as opposed to social support, that is entirely a micro-level phenomenon). Understanding what corresponds to the macro level and what corresponds to the micro-level is the first step that any researcher in social capital must take.

In summary, the paper by Carrillo and Riera offers a very useful guideline for the measurement of social capital at different scales. Researchers will be well served by following their prescription regarding measurement tools and conceptualizations. Nonetheless, as we have argued before (Carrasco and Bilal, 2016a) researchers will be also well served by (a) doing an explicit declaration of the theoretical framework they use to conceptualize social capital and (b) thinking of the consequences of using alternative frameworks.

Usama Bilal is a PhD Candidate in Cardiovascular Epidemiology at the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health. I am interested in the effects of macrosocial and local change on cardiovascular risk factors. I acted as a journal reviewer for the paper by Carrillo and Riera.

Usama Bilal is a PhD Candidate in Cardiovascular Epidemiology at the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health. I am interested in the effects of macrosocial and local change on cardiovascular risk factors. I acted as a journal reviewer for the paper by Carrillo and Riera.

References

Bourdieu, P. (1986). The forms of capital. Readings in economic sociology, 280-291.

Carrasco, M.A., Bilal, U. (2016a). Are subversion and conflict component parts of social cohesion?: A reply to Lindstrom. Social Science & Medicine. 169, 31-32.

Carrasco, M.A., Bilal, U. (2016b). A sign of the times: To have or to be? Social capital or social cohesion? Social Science & Medicine. 159, 127-131.

Carrillo Álvarez, E., Riera Romaní, J. (2016). Measuring social capital: further insights. Gaceta Sanitaria,

Cummins, S., Curtis, S., Diez-Roux, A.V., Macintyre, S. (2007). Understanding and representing ‘place’ in health research: a relational approach. Soc Sci Med. 65 (9), 1825-1838.

Edwards, J.K., Cole, S.R., Westreich, D. (2015). All your data are always missing: incorporating bias due to measurement error into the potential outcomes framework. International journal of epidemiology. 44 (4), 1452-1459.

Lindström, M. (2016). Are subversion and conflict component parts of social cohesion? Social Science & Medicine. 169, 106-108.

Villalonga-Olives, E., Kawachi, I. (2015). The measurement of social capital. Gaceta Sanitaria. 29 (1), 62-64.